Work Will Never Be the Same, Neither Will Cities

A Watershed Moment

The month was March, 2020. I was working in a beautiful high-rise office in downtown San Francisco. And just outside the Golden Gate bridge, a cruise ship named the Grand Princess held over 700 sick passengers, who had all contracted a new virus called Covid-19. At the time, there were just over 1,000 confirmed Covid cases in the world outside of China. On Monday March 9th, my coworkers and I gathered at the windows in awe, as the Grand Princess sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge, escorted by a detail of police boats. The pandemic had arrived. The following Friday, HR announced a temporary work-from-home policy, and that was my last day in the office.

Of course, we weren’t alone. If you worked in an office at the start of March 2020, by the end of the month you were working in the same place I was: at home. Two years later, people are, ever so gradually, returning to the office. But there’s a catch. Most people enjoyed working from home. For the record, I’m not actually one of those people. I’ve always enjoyed working from an office. But when it comes to forecasting national trends, how I feel is sadly irrelevant. There are three options available now, returning to the office 100%, exclusively working remotely, and a hybrid option. As a tautology, I can promise that we’ll end up with one of these three options. Predicting which option becomes the norm requires further investigation.

What Do People Want

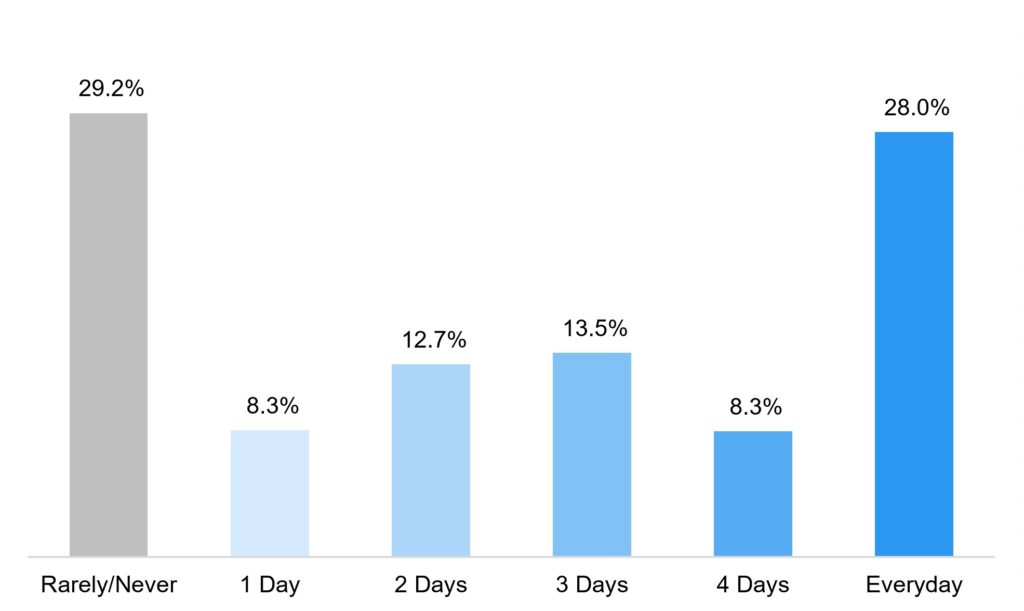

Perhaps most important is how people feel about their working options. If all employees and employers were adamant about returning to the office, what should happen is irrelevant because we know what would happen and vice versa. A group appropriately named WFH Research has been collecting survey data about people’s expectations for remote work options. Below is a summary of expectations for how many paid, work-from-home days employees would like to have per week, once the pandemic is over.

WFH Post-Pandemic Expectations – All Employees

There are two ways to look at this data. First, you can say that roughly as many people want to go back to the office as want to never step foot in an office again. Alternatively, you can say that 71% of people want to work at home more than they did prior to the pandemic. For reference, only 5% of work was done remotely before 2020. However, this dataset is for all jobs and not all jobs can be done from home. If you’re a pilot by trade, it doesn’t really matter if you want to work from home, unless you live in an airplane. Looking only at people who believe that their jobs can be done remotely, the results become even more skewed towards working from home.

… 71% of people want to work at home more than they did prior to the pandemic.

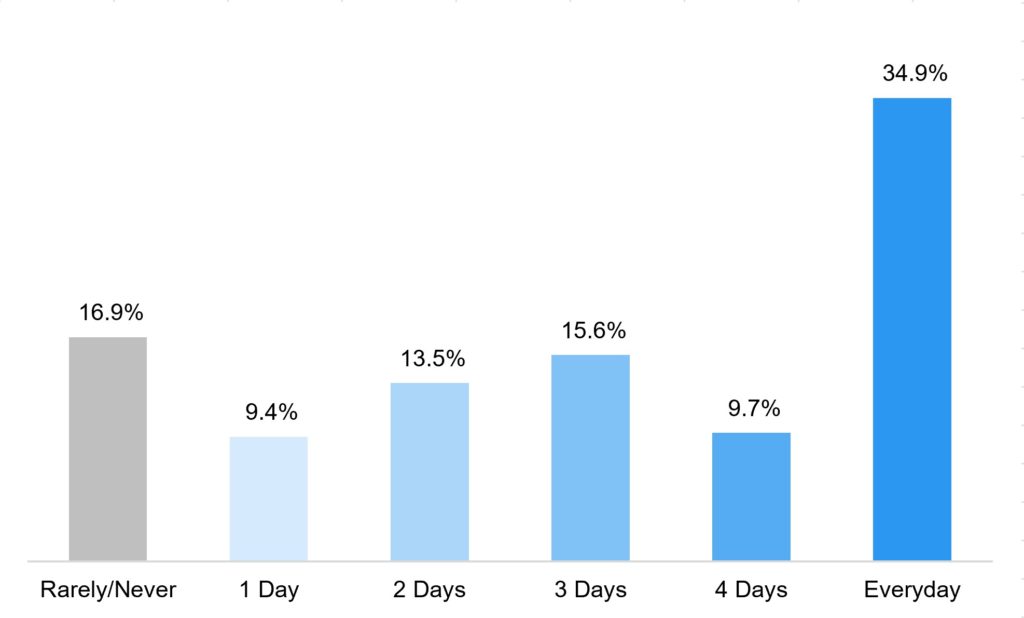

WFH Post-Pandemic Expectations – Possible Remote Jobs

In fact, 83% of employees, who believe that their jobs can be done remotely, want to work from home at least one day per week. Interestingly, you can also control for employees who don’t believe that their jobs can be done remotely.

… 83% of employees, who believe that their jobs can be done remotely, want to work from home at least one day per week.

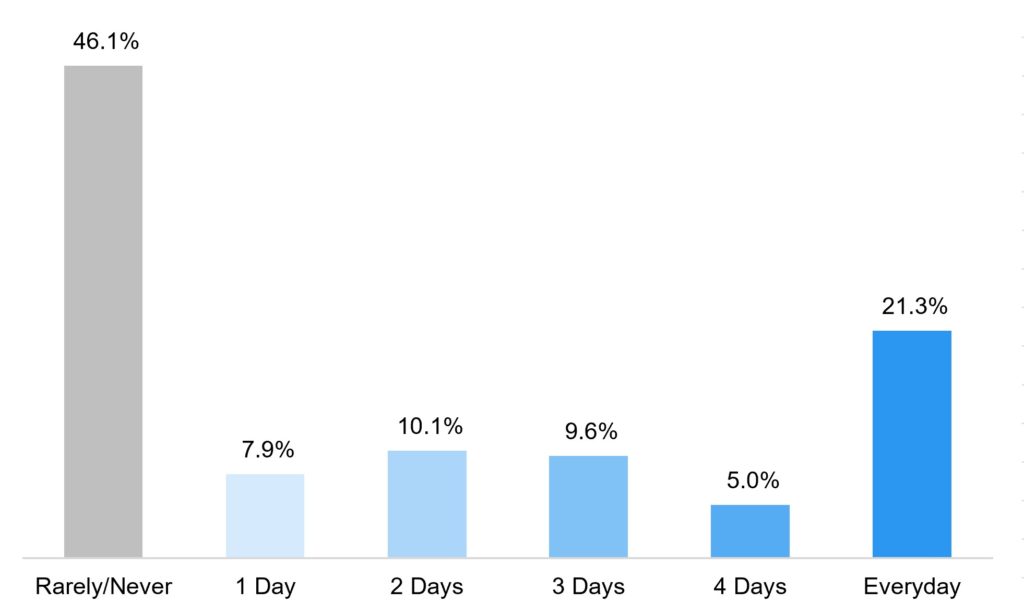

WFH Post-Pandemic Expectations – Non-Remote Jobs

This chart isn’t particularly germane to the discussion, but part of me appreciates that 21% of people admit that their jobs can’t be done remotely and also want to “do” their jobs remotely. In all seriousness though, this result may speak to the overall sentiment towards working from home; many people view it favorably compared to working onsite.

However, there are two sets of opinions at play: employees and employers. And unsurprisingly, employers are more likely to want employees back in the office. I’ve seen some articles even claim that there is a “great divide” between CEOs and their employees when it comes to remote work. But digging into the data, the gap is small where it matters. For jobs that can be done remotely, employees expect to work at home three days per week on average, while employers are planning for an average of two and a half days at home. Half a day hardly seems like a “great divide”. The disparity that most articles focus on may come from that stubborn 21% of people who want to work remotely even though their jobs preclude it. In all, sentiment seems to favor an environment where people end up working from home much more than they did prior to the pandemic, whether that’s via a hybrid option or 100% remote work. 1

For jobs that can be done remotely, employees expect to work at home three days per week on average, while employers are planning for an average of two and a half days at home.

Short Term Shock or Long Term Trend

In the short run, sentiments from both employees and employers hint that working from home will remain common, though whether this change is a new equilibrium is yet to be seen. Over the long-run, jobs could still trend towards returning to the office. The long run arguments for remote work are simple: wellbeing and productivity. Most people enjoy working from home, and remote workers don’t waste time commuting. All else equal, not commuting allows people to be more productive, simply by giving them more hours in the day. The long-term counter argument to remote work usually stems from looking at the status quo of pre-pandemic life. Modern telecommunication technologies, such as videoconferencing, weren’t invented alongside the discovery of Covid. If people had the technology to work remotely before the pandemic, why didn’t they?

I’ve heard several people (myself included) make the argument that remote work hampers career growth. Intuitively, you increase your chances of a promotion if you get more facetime with the people in charge of promotions. Career trajectories of at-home versus in-office employees will be studied for years to come, but right now, there simply isn’t good data. It’s too early to tell if this argument has merit. One study I’ve seen cited in several articles was done prior to the pandemic. Employees were randomly assigned to work from their home or in the office. In terms of raw data, if two workers were equally productive, the in-office worker was more likely to receive a promotion. However, at-home workers were on average more productive, and thus they were promoted at the same overall rate as their office-dwelling colleagues. Even more interestingly, many of the at-home workers reported that they didn’t apply for a promotion because getting one would have forced them to return to the office.2 Perceptions about remote work have also shifted since this study. Working from home carries less of a stigma now. Thus, early data points indicate that remote workers won’t be penalized, or at least not severely, when they apply for promotions. However, I’ll admit that I think there’s always going to be some proximity bias when it comes to giving and getting promotions.

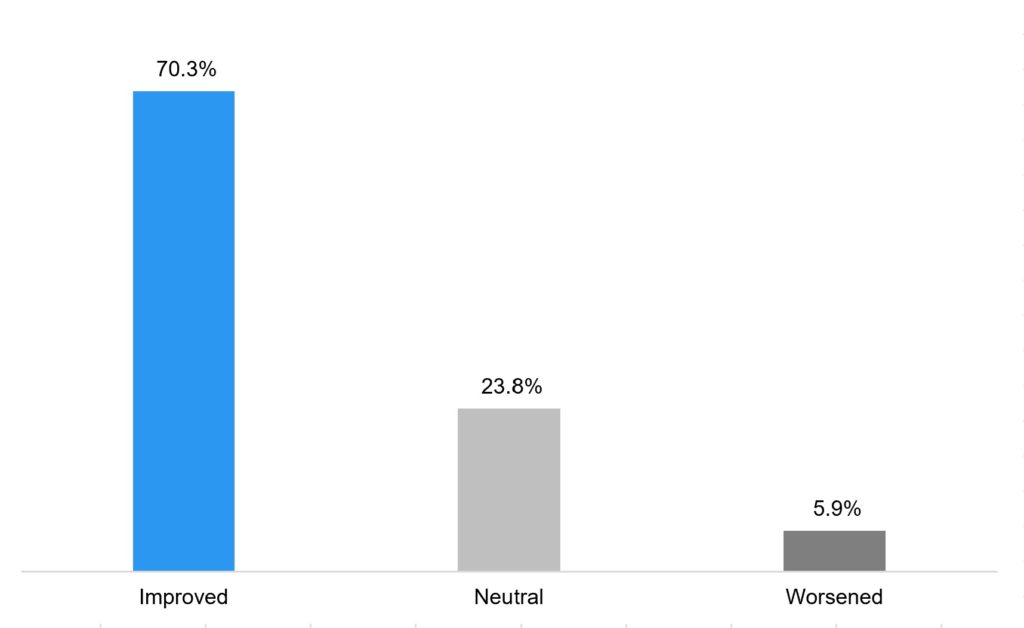

Since the COVID pandemic began, how have perceptions about working from home

changed among people you know?

… early data points indicate that remote workers won’t be penalized… when they apply for promotions.

From a different angle, one of the most compelling cases I’ve heard for a long-term trend toward returning to the office is that telecommunication technologies have historically served as compliments to in-person interaction rather than as substitutes. The theory is essentially that people develop a better rapport face to face; there’s non-verbal communication that takes place in-person, which can’t be replicated, even over video. And once a personal connection is established, technology allows people to increase their total amount of communication between one another. Therefore, it follows that people and businesses are ultimately more productive with at least some level of in-person communication.

Whether telecommunication technology is a compliment or a substitute for in-person interaction is perhaps the central question about the long-term viability and prevalence of remote work. My personal stance is that telecommunication technologies are both a substitute and a compliment to in-person interactions. They’re a good substitute for routine interactions, such as meeting with your team to go over a weekly agenda. And they’re a compliment for new and novel interactions, letting you more easily stay in contact with people you’ve otherwise gotten to know face-to-face. More broadly, not all interactions are created equal. Some communications are most effectively done in-person, and others are done more efficiently over Zoom.

Some communications are most effectively done in-person, and others are done more efficiently over Zoom.

WFH's Impact on Cities

Forever tied to where people work is where they live. For the last twenty years, we’ve seen “star” cities thrive because of their ability to attract talented workers. But this trend has created a funny duality in dense, high-cost-of-living cities. The people who pay the most to live there need to live there the least. Expensive cities contain lots of high paying jobs, most of which could be done remotely. 3 So now that remote work is prevalent, will people continue to pay high rents to live in cities like New York and San Francisco? The future for these cities may ultimately come back to the question of whether telecommunicating is a substitute or a compliment to in-person interaction.

Expensive cities contain lots of high paying jobs, most of which could be done remotely.

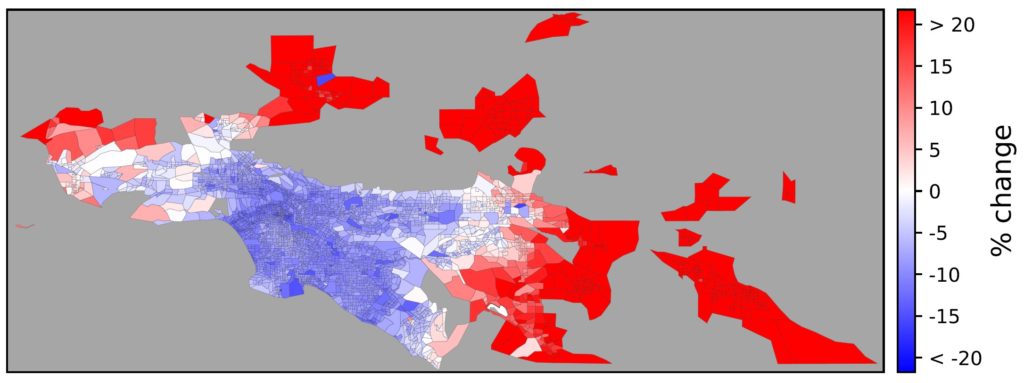

If telecommunication is a true substitute, we should see more and more firms adopt 100% remote work policies in the future, and as a result, people would flee expensive cities for ones with a more reasonable cost of living. This dispersion in turn would create a leveling effect. Cities such as San Francisco and New York that have both a very high cost of living and a large portion of jobs that can be done remotely would see real estate prices fall or stagnate, while smaller, lower-cost cities would see prices and populations climb.4

In the case where telecommunication is a compliment to in-person interaction, and not a substitute, people won’t be able to fully detach themselves from high-cost-of-living areas, even if companies implement a hybrid work model long term. Instead of heading to cheaper cities, people would head to cheaper parts of the city, looking for more space to live and work and taking advantage of less congestion, which would make longer commuting distances tenable. This fanning out effect would cause regions far from the city center to appreciate, while lowering the proximity premium of buildings in the inner core. In turn, because fewer people would commute every day, demand for office space would drop, demand for residential space would rise, and cities would be able to support a higher working population on existing commuting infrastructure. In this scenario, we would end up with the largest densest cities growing in overall population, with most of the growth occurring at the periphery.5

In reality, we’ll likely see (and have already seen) some of a leveling effect between cities and some of a fanning out within them. Not all jobs are created equal. For some jobs, telecommunication is a near perfect substitute for in-person work. If prior to the pandemic, you sold SaaS to international companies, you were effectively telecommuting already, even if you were required to telecommute from an office. Alternatively, if your work hinges on team rapport and a strong local network, you’ll benefit from being able to meet in-person, at least some of the time and maybe all the time. My guess is that the influx/outflux of large cities roughly cancels out, but people are more likely to live farther away from downtown than before the pandemic.

… we’ll likely see (and have already seen) some of a leveling effect between cities and some of a fanning out within them.

For certain, there will be a “new normal” that includes more remote work than prior to the pandemic. There’s no going back to 2019 because the shift we experienced in 2020 can’t be undone. A 2017 study of commuters in London found that when their primary commuting lines closed because of a labor strike, many people stayed with their alternative commuting routes after their original routes re-opened. 6 Everyone was forced to explore new commuting alternatives, and some people discovered better routes. That’s the post-pandemic world of work. Covid could disappear overnight, but the new pathways we’ve explored because of Covid can’t be forgotten. We’ve been forced to find which paths worked better all along.

- WFH Research | Survey of working arrangements and attitudes. (n.d.). Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://wfhresearch.com/

- Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., & Ying, Z. J. (2013). Does working from home work? evidence from a Chinese experiment. https://doi.org/10.3386/w18871

- Lukas Althoff, Fabian Eckert, Sharat Ganapati, Conor Walsh (2020). The City Paradox: Skilled Services and Remote Work. Munich Society for the Promotion of Economic Research. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3744597

- Brueckner, J., Kahn, M., &; Lin, G. (2021). A new spatial hedonic equilibrium in the emerging work-from-home economy? NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH. https://doi.org/10.3386/w28526

- Delventhal, M., Kwon, E., &; Parkhomenko, A. (2020). How do cities change when we work from home? SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3746549

- Larcom, S., Rauch, F., & Willems, T. (2017). The benefits of forced experimentation: striking evidence from the London underground network. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(4), 2019-2055.

More Insights

A look at Cloudline’s market selection process. What are the demand drivers we should be focusing on and how do they compar across major markets?

posted 2/18/2022

Supply is often just as important as demand, and even a great market can still be overpriced.

posted 2/18/2022

All about how syndications work, from start to finish.