On Peak Inflation and Recessions: Are we there yet?

Why Inflation Is So Important (Other Than the Obvious)

To be clear, the obvious reasons to care about inflation are your income and your savings. If you didn’t get a raise last year, you took an 8% pay cut. If you have money sitting in a bank, it lost +8% of its value last year (still better than being in the stock market I guess). In a normal economy, a little bit of inflation is good and necessary. Like repotting your houseplants, giving a plant (the economy) a bigger pot (some inflation) allows it to grow comfortably. You can’t have an expanding economy with a fixed amount of money. But inflation gets dangerous when it goes above what’s needed for growth. If inflation gets too high, it weighs on everyone’s financial decisions and erodes value. In extreme cases, hyperinflation can destroy people’s faith in the value of money, and at that point the only option may be to scrap the “currency” and completely and start over, like Brazil did in the nineties.

Luckily the U.S. isn’t anywhere near hyperinflation, but we are in a “danger zone”. Inflation can generate what’s called a wage-price spiral, which is a bit like a feedback loop. Let’s say you need a new fridge, but you can probably wait a year until your old one gives out. If you think prices are going to rise 10% in the next year, it makes sense to buy a new fridge now. And it also makes sense to bargain for a 10% raise at work because the cost of living is going up by 10%. Prices rise, and then everyone expects prices to rise, which in turn makes prices rise more – a wage-price spiral.

I can’t speak for Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, but fear of a wage-price spiral is likely why the Federal Reserve has acted so quickly raising interest rates. Recent inflation hasn’t shifted long-term expectations all that much, but it’s starting to. Ten-year expected inflation rose from 2.2 percent in 2019 Q4 to 2.8 percent in 2022 Q3 (1). If expectations rise more, inflation becomes a self-generating monster. Inflation needs to fall before people’s long-term expectations rise, which unfortunately means that the lashings (rate increases) will continue until moral (inflation) improves.

Inflation needs to fall before people’s long-term expectations rise, which unfortunately means that the lashings (rate increases) will continue until moral (inflation) improves

How Did We Get Here

To understand how and when we get out of this mess, we need to have at least some understanding of what is and isn’t causing inflation. In short, it’s a combination of supply chain issues, coupled with a very strong job market, coupled with too much money floating around in the economy. Any one of these problems would have created some inflation; having all three made inflation a major issue.

If you’ve spent any time on Twitter recently, you’ve probably seen people claiming that inflation is caused by corporate greed. Depending on how you look at the world, there’s some truth to that statement; after all, someone has to be raising prices, right? But this is a symptom not a cause. Inflation occurs when you have too much money chasing too few goods. Companies always want to raise prices, but most times they can’t. Perhaps most importantly, preventing companies from raising prices would only make matters worse. Want to know how Brazil ended up with such bad inflation that they had to dismantle their entire currency and start over? One misstep was freezing prices without freezing wages. As soon as price freezes ended, inflation came back worse than before.

Have We Reached Peak Inflation?

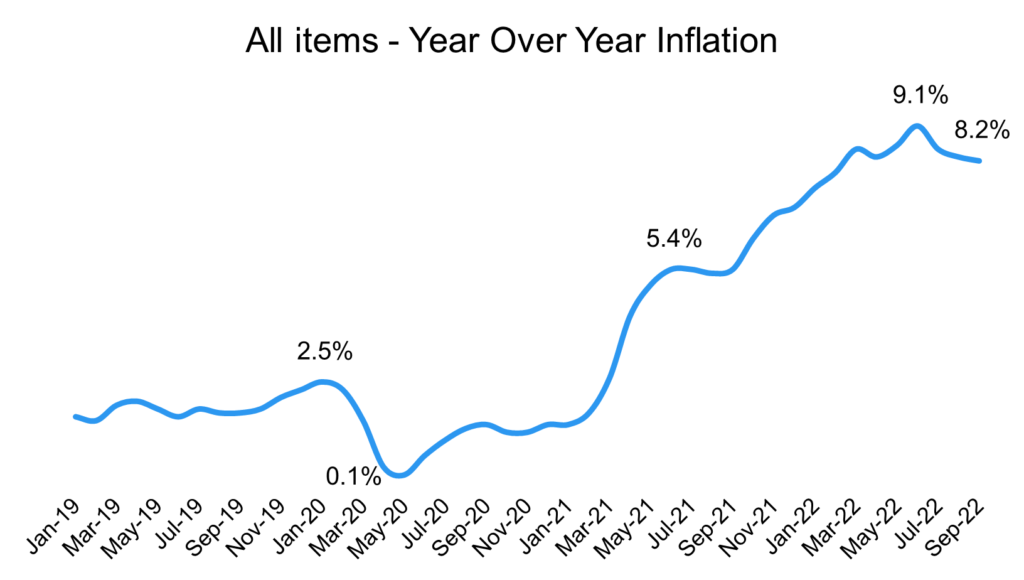

To oversimplify a complex topic, for inflation to go down prices need to go down or at least stop rising as quickly. If inflation has already peaked, we should see some softness in prices. First, let’s look at overall prices.

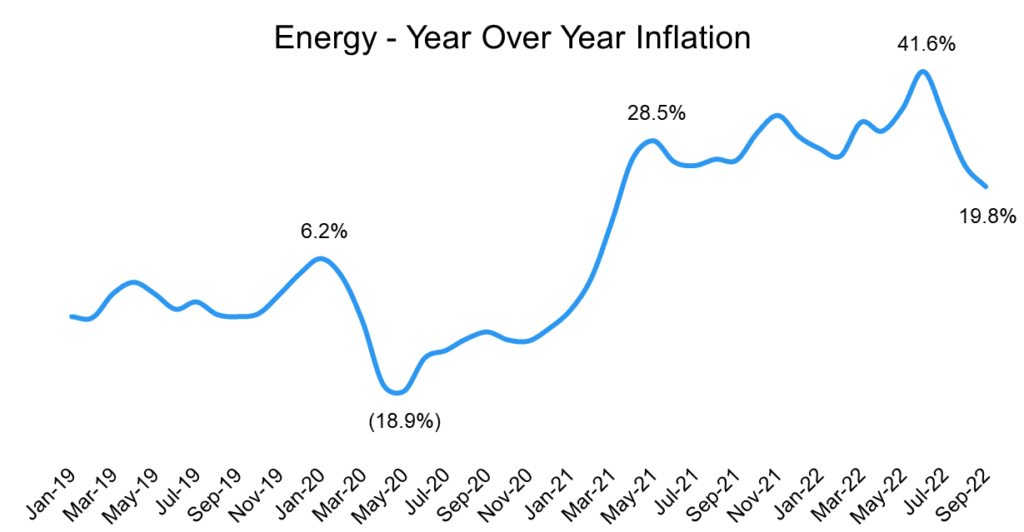

Good news! Sure, overall inflation is still at 8.2%, but that’s come down from 9.1%. Rome wasn’t built in a day, and reigning in +9% inflation takes time. There’s at least a chance that this inflation wave has already crested. Looking at individual price categories, a large piece of this “drop” in inflation comes from energy prices.

Energy prices went from really bad to just bad, but things are moving in the right direction. Energy costs have been a huge driver of the world’s inflation problems. Energy also tends to have a pass-through effect on other prices. Shipping and producing goods usually require energy, and as such, high energy prices get passed through to consumers.

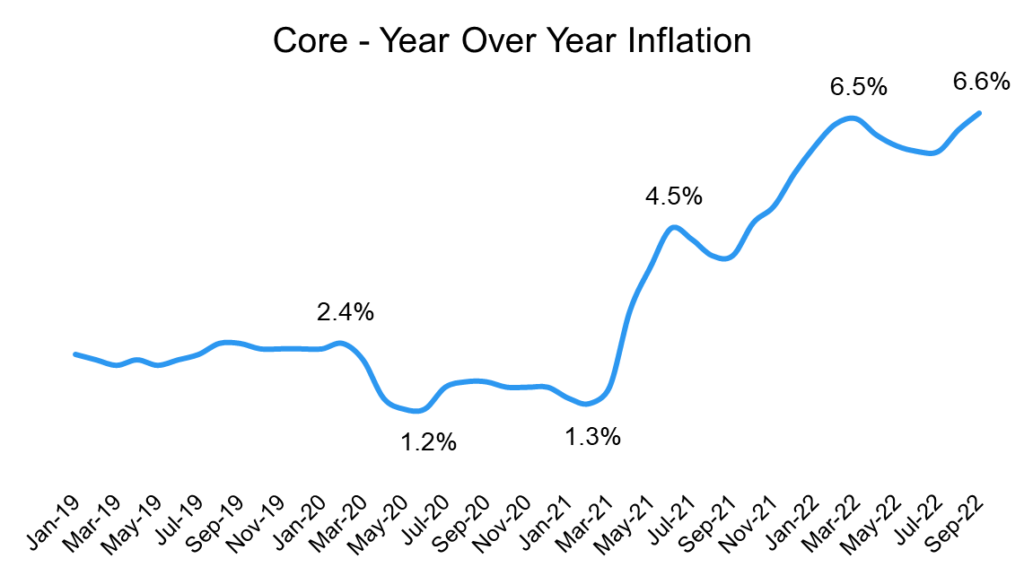

Energy prices might just be swinging wildly because that’s what energy prices do… Core inflation tends to be a better measure of overall inflation trends.

The caveat on energy prices is that they’re volatile. You don’t need to be a statistician to look at the graph and see just how volatile energy prices can be. In the last three years, energy prices have had annual changes between +42% and -19%. So, we shouldn’t assume that two months of falling energy prices mean anything. Energy prices might just be swinging wildly because that’s what energy prices do. Along with food prices, energy prices are so volatile that many economists exclude them from inflation data. Inflation excluding energy and food is known as “core” inflation. Core inflation tends to be a better measure of overall inflation trends.

Now this looks like more of a mixed bag. Unlike inflation on all items, core inflation is still trending upwards. If energy prices continue their decline, we’ll likely see core inflation start to come down due to the passthrough effect mentioned above. But if energy prices bounce around, we probably haven’t reached peak inflation yet.

What It Means for the Economy

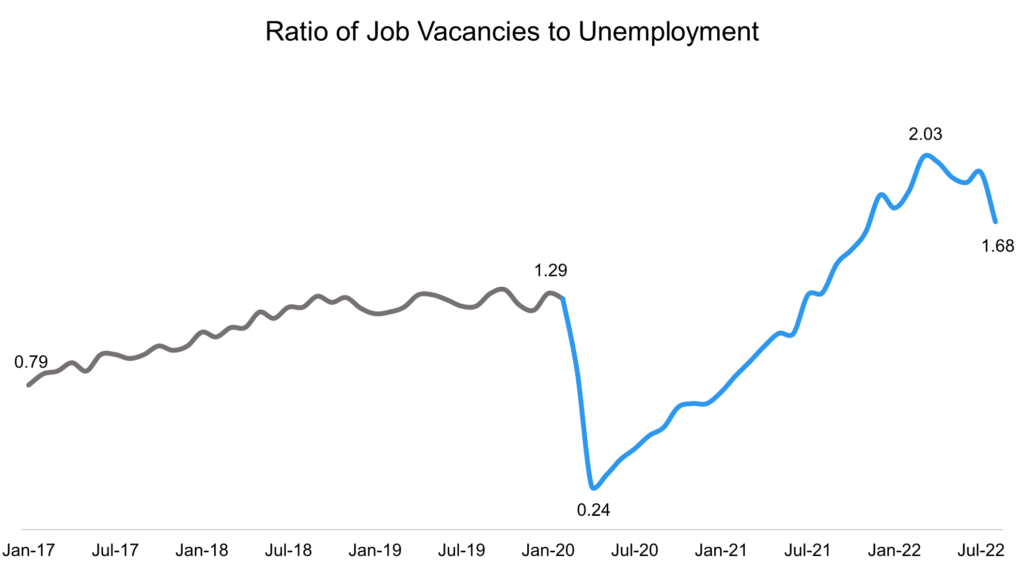

Prices are only one side of the inflation dance. People can’t continue to pay more if they simply don’t have the cash to do so. Along with financial aid packages that in hindsight were too generous and too numerous, a tight job market has been a major inflation driver. Right now, there are simply more jobs available than there are people to fill them.

Along with financial aid packages that in hindsight were too generous and too numerous, a tight job market has been a major inflation driver.

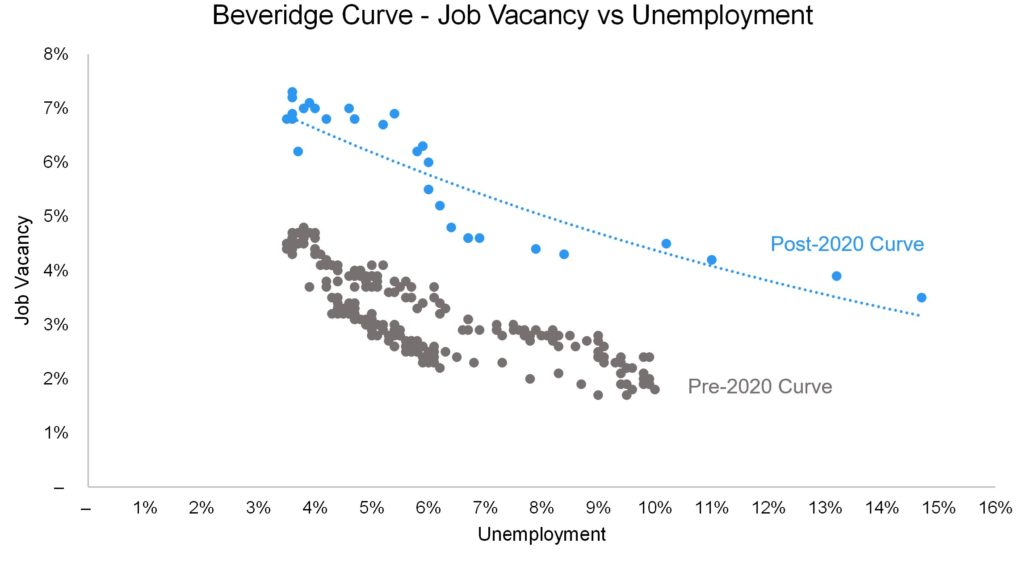

There’s some good news and some bad news here. The good news is readily apparent: the ratio of job vacancies is already declining. In a stable inflationary environment, that ratio tends to hover around 1:1, and in an attempt to cool inflation completely, the Fed may want to see the ratio dip well below 1:1. The issue is the relationship between job vacancies and unemployment. Vacancies and unemployment tend to move in opposite directions. If there are more job openings, there should be fewer unemployed people and vice versa. This relationship is what’s known as the Beveridge Curve.

This is going to get a little technical, but stay with me because this is the most important piece. For reasons that haven’t been completely flushed out and studied yet, the Beveridge Curve jumped outward at the onset of the pandemic and as of now hasn’t shown signs of returning to its pre-pandemic home. If this shift holds, it means the pandemic made the job market worse at matching job seekers to job openings. In turn, the natural unemployment rate would be higher, and current unemployment rate is going to have to get a lot worse in order to tame inflation. The Fed’s plan predicts peak unemployment of 4.1%. That prediction relies on the hope that the Beveridge Curve shifts back down to its pre-2020 levels, allowing job openings to decrease without unemployment spiking. However, if the Beveridge Curve stays where it is for the foreseeable future, unemployment could more closely follow former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers’ projection, where unemployment rises above 7% for two years.

The Fed’s plan predicts peak unemployment of 4.1%. That prediction relies on the hope that the Beveridge Curve shifts back down to its pre-2020 levels…

The Outlook

There’s one thing that seems almost certain to me: more rate hikes are coming. I expect an additional 75 point increase next week and additional 50-75 point increases in December and January depending on what inflation does between now and then. While there are plenty of people who think the Fed is moving too quickly, the threat of a wage-price spiral requires swift action. The Fed is fighting against the clock. If long-term inflation expectations continue to rise, that will only prolong inflation. And given mixed data on where inflation is headed right now, expect the Fed to continue increasing interest rates.

I expect an additional 75 point increase next week and additional 50-75 point increases in December and January…

The fallout from all these interest rate increases is largely dependent on how much the Beveridge Curve moves back towards its 2019 position. And while there’s no data to suggest that the curve is moving(2), you can easily make a case for why the last two years have been an exception. Disruption begets disruption. When Covid threw the world into lockdowns, people got a new perspective on their life and career choices. Many people moved cities and made switched jobs. Both changes would shift the Beveridge Curve out. But as people continue to settle into a post-covid balance, they probably won’t make major lifestyle and career changes more often than they did in 2019.

That said, even if the employment market starts functioning more like it did in 2019, that change will take time. All the employment shifts that have happened over the last two years should cause some lingering effects. After all, someone who started a new job two years ago is more likely to quit or get fired than someone who’s been working in the same job for +10 years. In all, we’re probably looking an economic downturn spanning the next two to three years where employment peaks between 5-6%. I wish I had something funny or hopeful to go out on here, but that’s not happening. This article is all about looking at reality on reality’s terms, and right now we have an unfortunate reality. The best thing to do is be prepared.

In all, we can probably expect an economic downturn spanning the next two to three years where employment peaks between 5-6%.

- Survey of Professional Forecasters

- Blanchard, O., Domash, A., & Summers, L. H. (2022). Bad news for the Fed from the Beveridge Space. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4174601

More Insights

A look at Cloudline’s market selection process. What are the demand drivers we should be focusing on and how do they compar across major markets?

posted 2/18/2022

Supply is often just as important as demand, and even a great market can still be overpriced.

posted 2/18/2022

All about how syndications work, from start to finish.